A Report on Torture and Human Rights Abuses in Zimbabwe

December 2007

The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa

The Open Society Institute

The Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture

Since early 2007, the Zimbabwean government has brutally sought to suppress political opposition with state sponsored torture and political violence. This upsurge in political violence occurred following a peaceful prayer rally organized on March 11 2007 by a coalition of Zimbabwean church and civic organizations.

This investigation, the first conducted by international health professionals since the March 2007 violence, provides evidence that the Zimbabwean government is systematically utilizing torture and violence as a means of deterring political opposition. This state-sanctioned violence targets low-level political organizers and ordinary citizens, in addition to the prominent members of the political opposition.

This report, based on forensic evaluations, documents how victims of political violence have been tortured and subjected to other human rights abuses causing devastating health consequences. Victims were detained under inhuman conditions and denied appropriate access to medical and legal assistance. Members of civil society, including doctors and lawyers assisting victims of political violence, also described being subjected to harassment by government authorities. These findings raise profound concerns as to whether elections scheduled for 2008 will be free and fair.

1. Robert Mugabe's threat to Trade Unionists before the 1998 strikes

Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa 12th Floor Braamfontein Centre 23 Jorissen Street

Braamfontein 2017

PO Box 678

Wits 2050 South Africa

Telephone: +27 (011) 403-3414/ 5/ 6

Fax: +27 (011) 403-2708

Email: info@osisa.org

Website: www.osisa.org

Open Society Institute

400 West 59th Street

New York, NY 10019

USA

Tel. 1-212-548-0600

Fax: 1-212-548-4619

Website: www.soros.org

Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of

Torture

462 First Avenue, C and D Building, Room

710

New York, NY 10016 USA

Telephone: 212-994-7169

Fax: 212-994-7177

Email: ask45@aol.com

www.survivorsoftorture.org

The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa

The Open Society Institute

The Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture

"We have degrees in violence" A Report on Torture

and Human Rights Abuses in Zimbabwe

A Report by

The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa

The Open Society Institute

The Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture

December 2007

Contents

Acknowledgements 1

I. Summary 2

Findings 2

Recommendations 3

II. Methods 5

Interviews with Primary Sources 5

Definitions Used 5

Consent Obtained 6

Secondary Sources 6

III. Background 6

IV. Trauma Experienced by Investigation Participants 11

Nature of Traumatic Events Experienced 11

Health Consequences of Torture/Political Violence Experienced 11

V. State Sponsored Torture and Violence after March 11 12

Political Violence and the Events of March 11 12

Violence Against Women 15

Violence and the Funeral of Gift Tandare 18

Continued, Targeted Political Violence 19

Complicity of Cio, War Veterans and ZANU-PF Youth post-March 11 21

Increased Harassment and Fear post March 11 23

Hardship and Fear for Zimbabwean Refugees in South Africa 25

VI. Photographs: Victims of Political Violence and Torture 28

VII. Health Consequences of Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe 33

Physical Health Consequences of Reported Abuses 33

Psychological Effects 35

Psychological Distress among Zimbabwean Refugees in South Africa 38

VIII. Poor Conditions of Detention and Delays in Access to Medical Care

and Legal Assistance 39

Inhuman Jail Conditions 39

Delays in Access to Legal Services while in Police Custody 40

Delays in Access to Medical Care while in Police Custody 41

Delays in Medical Care Outside of Prison 43

Difficulties Accessing Medical Care in South Africa 44

IX. Harassment of Doctors and Lawyers Assisting Victims of Torture and

Political Violence in Zimbabwe 45

Intimidation and Harassment of Doctors 45

Intimidation and Threats to Lawyers 47

X. Risks and Limitation of this Investigation 48

XI. Tables 49

The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa

(OSISA)

The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) is a leading Johannesburg-based foundation established in 1997, working in ten Southern Africa countries: Angola, Botsawanta, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. OSISA works differently in each of these ten countries according to local conditions.

There are specialized programme managers in Angola, Zimbabwe and Swaziland-these being the three countries in which significant structural

governance questions still obtain. OSISA is part of a network of autonomous foundations, established by George Soros, located in Eastern and Central Europe, the former Soviet Union, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and the US.

OSISA's vision is to promote and sustain the ideals, values institutions and practice of open society. OSISA's vision is that of a vibrant Southern African society in which people, free from material and other deprivation, understand their rights and responsibilities and participate democratically in all spheres of life.

In pursuance of this vision, OSISA's mission is to initiate and support programmes working toward open society ideals and to advocate for these ideals in Southern Africa. This approach involves looking beyond

immediate symptoms, in order to address the deeper problems – focusing on changing underlying policy, legislation and practice, rather than on short-term welfarist interventions.

Given the enormity of the needs and challenges in the region it operates in, and acknowledging that it cannot possibly meet all of these needs, OSISA, where appropriate, supports advocacy work by its partners in the respective countries, or joins partners in advocacy on shared objectives and goals. In other situations, OSISA directly initiates and leads in advocacy interventions, along the key thematic programmes that guide its work. OSISA also intervenes through the facilitation of new and innovative initiatives and partnerships, through capacity building initiatives as well as through grantmaking.

OSISA Johannesburg Office

12th Floor Braamfontein Centre

23 Jorissen Street

Braamfontein 2017

PO Box 678

Wits 2050 South Africa

Telephone: +27 (011) 403-3414/5/6

Fax: +27 (011) 404-2708

Email: info@osisa.org

Website: www.osisa.org

The Open Society Institute (OSI)

The Open Society Institute (OSI), a private operating and grantmaking foundation, aims to shape public policy to promote democratic governance, human rights, and economic, legal, and social reform. On a local level, OSI implements a range of initiatives to support the rule of law, education, public health, and independent media.

At the same time, OSI works to build alliances across borders and continents on issues such as combating corruption and rights abuses.

OSI was created in 1993 by investor and philanthropist George Soros to support his foundations in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Those foundations were established, starting in 1984, to help countries make the transition from communism. OSI has expanded the activities of the Soros foundations network to other areas of the world where the transition to democracy is of particular concern. The

Soros foundations network encompasses more than 60 countries, including the United States.

OSI Initiatives

OSI's initiatives address specific issue areas on a regional or network-wide basis around the world. Most of the initiatives are administered by OSI-New York or OSI-Budapest and are implemented in cooperation with Soros foundations in various countries and regions.

OSI initiatives cover a range of activities aimed at building free and open societies, including grantmaking to strengthen civil society; economic reform; education at all levels; human rights; legal reform and public administration; media and communications; public health; and arts and culture.

Soros Foundations

Soros foundations are autonomous institutions established in particular countries or regions to initiate and support open society activities. The priorities and specific activities of each foundation are determined by a local board of directors and staff in consultation with George Soros and OSI boards and advisors. In addition to support from OSI, many of the foundations receive funding from other sources.

The foundations network consists of national foundations in 29 countries, foundations in Kosovo and Montenegro, and two regional foundations, the Open Society Initiative

for Southern Africa (OSISA) and the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA). OSISA and OSIWA, which are governed by their own boards of directors and staffs from the region, make grants in a total of 27 African countries.

OSI-New York

400 West 59th Street

New York, NY 10019

USA

Tel. 1-212-548-0600

Fax: 1-212-548-4619

The Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture

The Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture provides comprehensive, multidisciplinary care addressing the medical, mental health, and social service needs of torture survivors and their families.

The program has established an international reputation for excellence in its clinical, educational, and research activities including documenting torture and its health consequences. The Bellevue/NYU Program is a

member of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims.

The Bellevue/NYU Program brings together clinical and academic resources from Bellevue Hospital, the oldest public hospital in the United States, and New York University School of Medicine. Since its inception in 1995, the program has cared for more than 2,000 men, women and children from over 70 different countries.

The Bellevue/NYU Program has conducted ground breaking research in documenting torture and its health consequences in countries around the world. Recent research projects have included evaluating the prevalence of trauma and psychological symptoms among Darfurian refugees in Chad; the health consequences of detention of asylum seekers in the United States; and trauma and its health consequences among Tibetan Refugees in India.

Recently, program staff have conducted forensic evaluations of former detainees from Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq and Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, Cuba.

The Bellevue/NYU Program its staff have received numerous awards including the Jim Wright Vulnerable Populations Award from the National Association of Pubic Hospitals, the Roger E. Joseph Prize from Hebrew Union College, The Barbara Chester Award from the Hopi Foundation, The Arthur C. Helton Human Rights Award from the American Immigration Lawyers Association, the Human Rights Defender Award from Physicians for Human Rights, and The Robin Hood Foundation Heroes Award.

Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture

462 First Avenue, C and D Building, Room 710

New York, NY 10016 USA

Telephone: 212-994-7169

Fax: 212-994-7177

Email: (Dr. Allen Keller-Program Director) ask45@aol.com

Website: www.survivorsoftorture.org

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was researched and written by Allen Keller, M.D., and Samantha Stewart, M.D. Dr. Keller is Associate Professor of Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, Director of the Bellevue/NYU

Program for Survivors of Torture, Director of the NYU School of Medicine Center for Health and Human Rights and is a member of the Advisory Board of Physicians for Human Rights. Dr. Stewart is a staff

psychiatrist with the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture, and an Attending Physician, Department of Psychiatry, Bellevue Hospital.

The report was reviewed and edited by Jonathan Cohen, Julie Hayes, Open Society Institute, New York, NY; Delme Cupido, Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa;

Bronwen Manby, The Africa Governance Monitoring and Advocacy Project, Open Society Institute, London, UK; Helen Epstein; and Dechen Lhewa and Jessica Kim, Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of

Torture, New York, NY.

We thank Dr. Loren Landau, Forced Migration Studies Programme, University of Witwatersrand, Witwatersrand South Africa; and Emily Sachs, Fordham University Department of Psychology New

York, New York, for their comments.

A special thanks to Selvan Chetty of Solidarity Peace Trust for all of his efforts and support in preparing this report. We are grateful to all of the individuals who agreed to be interviewed for this report and to all of the

individuals and organizations who provided information, advice and assistance in planning and preparing this report.

Support for this report was provided by the Open Society Institute.

2 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

I. SUMMARY

The 2008 Presidential campaign has already begun. This violence is the strategy of the ruling party. They want to eliminate opposition now so that the situation will appear calm in the period before the election. -Zimbabwean Human Rights Advocate

It is less than one year before Zimbabwe will hold the presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for March 2008. Since early 2007 the country has been subject to an upsurge in political violence that has

seriously undermined the democratic process and created a presumption that these elections will not be free and fair. State-sponsored violence directed toward any individuals or groups who are perceived to be

critical of President Robert Mugabe, his government or his policies, manifests a strategy to demobilize Zimbabweans from mounting or supporting an organized opposition campaign.

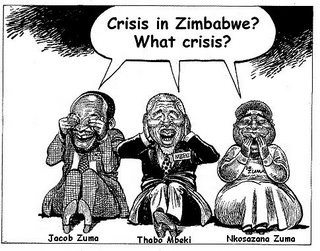

The international community and Southern African Democratic Community (SADC) have attempted to play a role in encouraging a democratic process by introducing South Africa's president, Thabo Mbeki, as a mediator between the ruling and opposition parties. However, the international community remains ineffective in its efforts to stop states-sponsored violence in Zimbabwe.

On March 11, 2007 a coalition of church and civic organizations known as the Save Zimbabwe Campaign, organized a prayer rally in Highfield, a township near the capital Harare. Police used violence and arrests to prevent the peaceful prayer rally. They shot to death an unarmed activist, Gift Tandare, and subsequently arrested several leaders of the major opposition party—the Movement for Democratic

Change (MDC)—as well as rank and file attendees.

While the brutal beatings and interference with medical care of the prominent MDC leaders following March 11 received considerable media attention, the persisting torture and political violence,1 particularly 1. For this report, individuals were classified as having been subjected to torture if the experience(s) they reported were considered by the examining physicians to meet criteria for torture as defined in the United Nations Convention Against Torture. (See Methods Section for complete definition).

Individuals were classified as having been subjected to political violence if the experience(s) they reported was considered, by the examining physicians, to be a violent act as a result of their political activities or beliefs, but which was not that perpetrated against rank and file political activists, have not been documented by international health and human rights experts. This report details the state-sponsored violence that occurred in the wake of the highly publicized events of March 11, 2007.

Researchers from the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture traveled to South Africa and Zimbabwe during the last week of April and first two weeks of May 2007 at the request of local

nongovernmental organizations to evaluate reports of torture and political violence. This report is based on the detailed testimony and medical examination of 24 individuals who were subjected to torture or political

violence during March and April 2007. Additionally, interviews were conducted with more than 30 health professionals, human rights advocates and representatives of non-governmental organizations in

Zimbabwe and South Africa.

This investigation, the first conducted by international health professionals with expertise in the evaluation documentation and treatment of torture victims since the March 2007 violence, provides evidence that the Zimbabwean government is systematically utilizing torture and violence as a means of deterring political opposition. This state-sanctioned violence targets low-level political organizers and ordinary citizens, in addition to the prominent members of the political opposition.

The medical evaluations of recent victims of torture and political violence document physical

and psychological evidence of violent human rights

abuses and the devastating health consequences of

such political violence. Victims were detained under

inhuman conditions and denied appropriate access to

medical and legal assistance. Members of civil society,

including doctors and lawyers assisting victims

of political violence, described being subjected to

harassment by government authorities.

Findings

In addition to prominent opposition leaders, ordinary

MDC members and local community organizers

are being systematically tortured and targeted by

Zimbabwean authorities for political violence. This

assessment is supported by the testimony and medical

evidence of the 24 Zimbabweans victims of torture

and political violence interviewed and evaluated for

considered, necessarily, to constitute torture.

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 3

this report. All had clear physical and psychological

evidence of torture and abuse corroborating their

testimony. These victims of political violence included

both men and women. They were not randomly

targeted, but included national and local leaders of

the political opposition, community organizers, and

ordinary citizens. Zimbabweans who were arrested

and detained for their political activities described

being detained under filthy, inhuman conditions as

well as being denied basic necessities such as food,

water, light, and blankets.

This torture and political violence has devastating

physical, psychological and social health

consequences. At the time of evaluation, all 24 of

the Zimbabwean victims of torture and political

violence evaluated for this report continued to suffer

from substantial and often debilitating physical and

psychological symptoms as a direct result of their

abuse. Individuals suffered from severe pain, broken

bones, and unhealed wounds as a result of beatings

they had endured. Their backs and legs showed clear

marks from whips or the imprints of clubs used to beat

them. The psychological scars, including depression,

post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and associated

symptoms such as profound sadness, nervousness,

difficulty sleeping, and recurrent memories of

the trauma were also evident. Victims frequently

described profound fear of further torture or death as

well as threats to their family.

Furthermore, Zimbabwean authorities are interfering

with and delaying access to medical and legal services for

victims of torture and political violence. News accounts

have neglected to describe the systematic interference

with access to medical and legal services for victims

of violence. Such interference not only infringes upon

the rights of these individuals and compounds their

abuse, but is designed to increase impunity for abuse

by preventing health workers and legal professionals

from evaluating and documenting the abuse. Many of

the Zimbabwean victims of torture/political violence

interviewed described experiencing substantial delays

in obtaining medical evaluation and treatment as well as

being denied access to their lawyers.

Doctors and lawyers assisting victims of torture and

political violence described being threatened and

harassed by police and other government authorities. For

example, medical and legal professionals we interviewed

received threatening phone calls both at their homes

and at work warning them not to interfere with state-

sponsored violence.

Finally, Zimbabwean victims of torture or political

violence fleeing to South Africa often endure

substantial difficulties in obtaining refugee status and

accessing health services. Zimbabwean victims of

political violence as well as Zimbabwean advocates

in South Africa described the many problems that

Zimbabwean refugees encounter upon their arrival in

South Africa. This includes problems with obtaining

refugee status or political asylum; problems with

attaining adequate food and shelter; difficulty getting

appropriate and necessary healthcare; and ongoing

fears of deportation and discrimination.

Recommendations

1. Recommendations to the Zimbabwean

Government:

Immediately cease and investigate all acts of

torture and state-sanctioned political violence

The Government of Zimbabwe should immediately

cease all acts of torture and state-sponsored violence,

conduct transparent and credible investigations of

all allegations of torture and violence and publicly

condemn such acts. There is an urgent need to

resolve the political impasse in Zimbabwe, and this

must begin with an end to state sanctioned political

violence, including torture, arbitrary arrest, and

targeting individuals for political violence based on

their political affiliations.

Although Zimbabwe is one of 51 countries that has

not ratified the UN Convention Against Torture, it is

party to several international treaties that specifically

prohibit torture, including The International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter

on Human and People's Rights. Furthermore,

Zimbabwe's own Constitution (Section 15) outlaws

torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment.

Ensure adequate and timely access to medical

and legal services for victims of torture and

political violence

Individuals suffering from injuries and illness in state

custody, including victims of torture and political

violence, must have access without delays to adequate

medical and legal services. The Government of

Zimbabwe must take immediate steps to protect

health professionals and legal service providers from

harassment and intimidation.

•

•

4 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

Ensure accountability and legal prosecution of

perpetrators of torture and political violence

Individuals, including police, ZANU-PF party

members and members of related organizations who

have participated in torture and political violence must

be held accountable in courts of law for their actions.

Independent investigations into the excessive use of

force on March 11 2007 as well as investigation of the

organizations responsible for this and subsequent

violence must be undertaken.

2. Recommendations to the Zimbabwean Medical

Association:

Speak out against violations of human rights

including torture, political violence and denial

of medical care to detainees

The Zimbabwean Medical Association (ZIMA) should

work to ensure that the Zimbabwean government

upholds nationally and internationally recognized

human rights standards including prohibitions of

torture and the provision of medical care for detainees.

Furthermore, ZIMA should see that physicians can

fulfill their professional obligations to maintain clinical

independence without harassment and intimidation.

3. Recommendations to African leaders and the

International Community:

Governments and international bodies

including members of the Southern African

Development Community (SADC), the United

Nations Security Council, and the United

Nations Commissioner on Human Rights

must hold the Zimbabwean government

accountable for its obligations under

international law regarding prohibition of

torture and political violence.

African and international leaders must strongly and

publicly condemn acts of torture and state sanctioned

political violence in Zimbabwe.

Medical and legal professional organizations

and nongovernmental organizations both in

Africa and internationally must condemn acts

of torture, state sanctioned political violence

in Zimbabwe, obstruction of access to medical

and legal services for detainees, and

harassment of medical and legal professionals

assisting victims of political violence.

•

•

•

•

Medical and legal organizations in Africa and

internationally, need to support colleagues operating

under duress and use all regulatory and professional

organizing bodies to call for internationally endorsed

standards for legal representation and provision of

medical care.

4. Recommendations to President Mbeki and the

South African Government

President Mbeki must provide strong

leadership in opposing torture and political

violence in Zimbabwe

President Mbeki must use his role as a democratic

leader in the Southern African community to uphold

international standards for opposition of torture

and political violence and promotion of free and fair

elections and basic human rights including a fair

and impartial judiciary and rights of detainees in

Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwean victims of torture and political

violence, for whom it is not safe in Zimbabwe,

should be granted political asylum

consistent with the protections of international

law. Appropriate access to medical, mental

health and social services should be ensured

South Africa must provide protection for

Zimbabweans fleeing persecution and political

violence. Given recent events and historical increases

in violence prior to Zimbabwean elections, the South

African Government and refugee organizations should

prepare for an increase in the number of Zimbabwean

victims of torture and political violence. Steps should

be taken to ensure basic and non-discriminatory access

to medical and social services.

•

•

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 5

II. METHODS

Interviews with Primary Sources

In April and May 2007, detailed medical evaluations

of 20 Zimbabweans reporting experiences of torture or

political violence in Zimbabwe since March 11, 2007

were conducted. The evaluations were performed

in Zimbabwe and in South Africa. In addition,

evaluations were conducted with 4 individuals

reporting torture or political violence during the year

preceding March 11, 2007. All respondents continue to

live in fear of further torture or political violence.

Seventy-nine percent of the Zimbabwean victims of

torture and political violence evaluated were male

and 21% were female (see Table 1: Demographic

Information). The mean age was 36 (range: 19-64), and

75% of the individuals were 40 or under. All but two of

the individuals were members of or politically active

with the MDC party. Those active with the MDC party

were primarily local organizers (12) rather than those

working at the national level (6). While many of the

victims were from Harare and Bulawayo, others came

from all parts of Zimbabwe.

Clinical evaluations were performed using established

international guidelines for investigating and

documenting torture and other cruel, inhuman or

degrading treatment or punishment.1 Detailed trauma

and medical histories were elicited by interview;

a detailed review of physical and psychological

symptoms was conducted; and physical examinations

were performed. These evaluations were conducted

by two physicians with extensive experience in the

evaluation and treatment of victims of torture and

political violence. Each evaluation took approximately

two hours. Interviews were conducted in English for

22 of the 24 individuals. For two individuals, Shona

interpreters were used.

In addition to clinical interviews, assessment of

psychological symptoms was conducted using

two self-report standardized questionnaires: the

1. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for

Human Rights. The Istanbul Protocol. Available at: http://

www.ohchr.org/english/about/publications/docs/8rev1.

pdf.; Iacopino V, Allden K, Keller A. Examining Asylum

Seekers. A Health Professional's Guide to Medical and

Psychological Evaluations of Torture. Boston: Physicians for

Human Rights; 2001.

Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 (HSCL-25)2 and

the post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) portion

of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ).3 The

HSCL-25 is a 25-item self-report scale comprised of

two subscales measuring anxiety and depressive

symptoms. Mean scores over 1.75 for the HSCL-25

identify individuals who are highly symptomatic.

The PTSD portion of the HTQ includes a 16-item scale

developed to quantify severity of PTSD symptoms.

Mean scores over 2.5 on the HTQ are associated with

a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. The HSCL-25 and HTQ

have been used extensively with diverse populations

in studies of trauma, and have been validated against

clinical diagnoses. Eighteen of the 24 victims of torture

and political violence evaluated in this investigation

completed these questionnaires. The remaining six

individuals did not do so because of time limitation.

Definitions Used

Individuals were classified as having been subjected

to torture if the experience(s) they reported was

considered, by the examining physicians, to meet

criteria for torture, as defined in the United Nations

Convention Against Torture.4 Individuals were

classified as having been subjected to political violence

if the experience(s) they reported was considered, by

the examining physicians, to be a violent act as a result

of their political activities or beliefs, but which was not

considered, necessarily, to constitute torture.

2. Derogatis LR, Lipman R, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi

L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report

symptom inventory. Behavioural Science. 1974;19:1-15.

3. Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S,

Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Validating

a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma,

and post-traumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees.

Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180:110-115.

4. United Nations General Assembly. Convention Against

Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

or Punishment. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/

english/law/cat.htm. According to the United Nation's

Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman

or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, torture is defined

as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether

physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person

for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person

information or a confession, punishing him for an act he

or a third person has committed or is suspected of having

committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person,

or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when

such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or

with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other

person acting in an official capacity."

6 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

III. BACKGROUND

During late 2006 and the beginning of 2007,

peaceful protests and anti government opposition

in Zimbabwe prompted an upsurge in violent

reactions by the police, resulting in the arrests and

beatings of students, trade union members and

human rights advocates. On September 13, 2006

police arrested and reportedly tortured 15 leaders

and members of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade

Unions (ZCTCU) after they attempted to hold a

peaceful protest concerning the deterioration of

the social and economic conditions in Zimbabwe.1

According to Human Rights Watch, in February

2007, at least 400 civil society activists and

opposition members were arrested for attending

peaceful demonstrations and organizational

meetings.2 On February 21, police imposed a three

month ban on political rallies, claiming that such

rallies would result in violence and a breakdown in

law and order.3

Then, on March 11, 2007, police violently disrupted

a prayer meeting in Highfield organized by a

coalition of civic and religious organizations called

the Save Zimbabwe Campaign. Police used tear gas,

water cannons and live ammunition against the

unarmed crowd.4 One crowd member, Gift Tandare,

was shot and killed. More than 50 others, including

the president of the major opposition party- the

Movement for Democratic Change (MDC)-Morgan

Tsvangirai, were arrested and reportedly beaten and

tortured. Since then repression in Zimbabwe has

only intensified.

1. Amnesty International. Amnesty International Report 2007.

Available at: http://thereport.amnesty.org/eng/Regions/

Africa/Zimbabwe; Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for

Human Rights (ZADHR). Torture and Denial of Access to

Treatment of ZCTU Members. Available at: http://www.

kubatana.net/html/archive/hr/060915zadhr.asp?orgcode=z

im065&year=2006&range_start=1.

2. Human Rights Watch. Bashing Dissent: Escalating Violence

and State Repression in Zimbabwe. May 2007. Available at:

http://hrw.org/reports/2007/zimbabwe0507/.

3. Ibid.

4. Timberg C. Opposition Leaders Arrested in Zimbabwe.

Washington Post. March 12, 2007. Available at: http://www.

washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/03/11/

AR2007031101520_pf.html

Examples of political violence included:

An unarmed individual being shot at a

demonstration

An individual witnessing someone being

beaten by police

An individual being threatened with arrest if

he/she continues their political activities

Examples of torture included:

An individual repeatedly beaten by police or

groups such as the Youth Militia

An individual threatened with death while in

police custody

Consent Obtained

Individuals verbally consented to be interviewed

and examined and to have the findings publicly

disseminated. No one was compensated for the

interviews or medical examinations. For safety and

privacy, victims are referred to in this report either

with pseudonyms or pseudo-initials.

Sekai Holland, who reported being tortured in

Zimbabwe following March 11, gave permission

for her name to be used. Several individuals who

provided background information requested not to be

identified.

Secondary Sources

In addition to these detailed medical evaluations,

background interviews were conducted with more

than 30 key informants in South Africa and Zimbabwe,

who were approached based on their knowledge

of the situation in Zimbabwe. This included health

professionals, lawyers, human rights advocates and

community organizers, many of whom are working

with non-governmental organizations in Zimbabwe

and South Africa. Individuals who requested

anonymity are not identified.

(See Chapter IX for Risks and Limitations of this

Investigation).

•

•

•

•

•

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 7

According to a report issued by Human Rights Watch:

The arrest and severe beating of these opposition leaders

and civil society activists by police and state security

officers marked a new low in Zimbabwe's seven-year

political crisis. It ignited a new government campaign

of violence and repression against members of the

opposition and civil society-and increasingly ordinary

Zimbabweans-in the capital Harare and elsewhere

through the country._

State-sponsored torture and political violence in

Zimbabwe are calculated to deter opposition in

the run-up to national elections and referenda, and

constitute a major threat to the country's democratic

development. In late March 2007, the "Mbeki

Initiative," was launched by the Southern African

Development Community (SADC) in an effort to

negotiate a resolution to Zimbabwe's eight-year

political and economic crisis. The initiative gave

South African president Thabo Mbeki the role of

facilitating dialogue between President Mugabe's

ZANU-PF government and the opposition MDC.

Useful talks have been marred by continued violence,

with President Mugabe asserting the violence is

government response to "terrorism."6

The report of quick and violent crackdowns on ZCTU

rallies in September and at the prayer rally on March

11th is consistent with a pattern of elevated violence

prior to past elections. Presidential and parliamentary

elections in Zimbabwe were moved forward to March

2008 shortly before the noted escalations in violence.

Additionally the reports from many of the victims

that their torturers are making anti-MDC statements

suggests that a campaign is underway to deter

political activism in the run up to the coming elections.

The current upsurge in state-sponsored violence has

the potential to intimidate and brutalize voter morale

in a country that continues to face severe declines

across all sectors.

Arguably, it is no coincidence that the escalation

in violence occurred precisely one year before

5. Human Rights Watch. Bashing Dissent: Escalating Violence

and State Repression in Zimbabwe. May 2007. Available at:

http://hrw.org/reports/2007/zimbabwe0507/.

6. Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum. Their Words Condemn

them: The Language of Violence, Intolerance and Despotism

in South Zimbabwe. May 2007. Available at: http://www.

hrforumzim.com/frames/inside_frame_special.htm.

the March 2008 Parliamentary and Presidential

elections. This supports the assertion that the torture

and political violence are the result of a deliberate

government policy to frighten into silence anyone

who might be considering supporting the opposition.

President Mugabe and the ruling ZANUPF party

have frequently stated that the opposition is being

supported by foreigners such as London-based groups

in league with the British government invoking

anti-imperialistic rhetoric. For example in interviews

conducted for this report, victims of torture and

political violence described being called "prostitutes of

Tony Blair." The rationale for such rhetoric likely has

far more to do with the internal Zimbabwean politics

than it does with Zimbabwe's relationship with Britain

or other foreign powers.

Torture and political violence results in fear and

terror that disseminates throughout the community

and entire country. In addition to the physical and

psychological impacts on the individual victims, such

torture and political violence sends a chilling message

to others: "Be silent or this could happen to you."

At least 459 cases of human rights violations have been

documented by human rights organizations between

March 11, and May 1, 2007.7 Dr. Douglas Gwatidzo,

Chairman of ZADHR noted the following:

What they are doing is targeting individuals that are

the leaders and organizers and secretaries that organize

groupings. They come in the middle of the night, pick

you up, beat you and leave you there. They don't care

if you die; that is one way they are beating people into

submission. March 11 was the peak, it came down, but

now it is a sustained level. They want people to be aware

if anyone dares oppose the government this is what is

going to happen to you8.

Dr. Reginald Matchaba-Hove of the University of

Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences, a leading public

health expert in Zimbabwe described the current

violence as follows:

7. Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, Zimbabwean

Association of Doctors for Human Rights. A Brief Report of

Human Rights Violations in Zimbabwe since March 11 2007.

Submitted to the African Commission on Human and

People's rights, May 2007.

8. Unless otherwise noted all quotes in this report come from

testimony collected by Bellevue/NYU researchers. Precise

interview dates and locations have been omitted for security

reason.

8 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

any threats of violence will be taken seriously by local

populations.

The upsurge in state instigated violence in Zimbabwe

since March 2007 has been documented by several

organizations including Human Rights Watch (HRW),9

Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights

(ZADHR),10 Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights

(ZLHR),11 the Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum12 and

Solidarity Peace Trust (SPT),13 a non-governmental

organization registered in South Africa. SPT compiled

information from independent interviews with 414

Zimbabwean victims of human rights abuses during

March, April and May 2007, including targeted

attacks against the leadership of the MDC and the

civic movement in Zimbabwe. In 90% of the attacks

the perpetrators involved government agencies such

as the police and Central Intelligence Organization

(CIO). MDC activists and leaders were frequently

targeted outside of police stations, and at times they

were taken from their homes. Eighty percent of the 414

interviewees in SPT's report had physical injuries, and

in all of these cases corroborating medical evidence

was documented. Soft tissue injuries were particularly

frequent, as were body aches and headaches, sleep

disturbances, anxiety and depression. Thirty percent of

these 414 individuals reported being victims of torture.

Access to necessary medical care for victims of political

violence was also a significant concern following

the events of March 11th. On March 13, 2007 ZADHR

reported:14

9. Human Rights Watch. Bashing Dissent: Escalating Violence

and State Repression in Zimbabwe. May 2007. Available at:

http://hrw.org/reports/2007/zimbabwe0507/.

10. Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, Zimbabwean

Association of Doctors for Human Rights. A Brief Report of

Human Rights Violations in Zimbabwe since March 11 2007.

Submitted to the African Commission on Human and

People's rights, May 2007. Also see following website for

several reports/statements relating to political violence since

March 11 2007: http://kubatana.net

11. Ibid.

12. Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum. http://www.

hrforumzim.com.

13. Solidarity Peace Trust. Destructive Engagement: Violence,

Mediation and Politics in Zimbabwe. Johannesburg, South

Africa: Solidarity Peace Trust. July 10 2007. Available at:

http://www.solidaritypeacetrust.org.

14. Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights.

Update on denial of access to treatment of detained activists.

March 13 2007. Available at: http://www.kubatana.net/

It is systematic. It is not random. It is not the use of

torture by police who are overzealous. It is not that there

was a demonstration and things got out of hand and this

is what happened. This is not the case. As we speak now,

there is still a stream of people who are specifically being

targeted.

A Bulawayo-based healthcare worker said:

We are concerned about more violence because the last

time we had any violence—the destruction of homes—it

started from Harare and then came here and it was very

severe. If it happened there, it will happen here. We are

an opposition region. If there is a campaign, it wants to

destroy any opposition. We are bound to suffer from that

violence as well. Because we are a region that has always

been opposed to the government in that manner the

government is likely to destroy us before the elections.

Following the disruption of the peaceful demonstrations

in Harare on March 11, 2007, torture and political

violence has escalated, much of it aimed at prominent

opposition leaders, particularly those affiliated with

the MDC. Several of these leaders, including Sekai

Holland and Grace Kwinje, senior MDC officials, were

evacuated to South Africa for medical care. The political

violence did not stop with these leaders, however,

raising concerns that the government has launched a

methodical campaign to eliminate any trace of political

opposition in Zimbabwe.

A human rights activist observed, "Zimbabwe allows

someone into parliament and then tortures them with

impunity. There hasn't been one single individual

charged."

Dr. Matchaba-Hove, who served as Chairperson of the

Zimbabwe Election Support Network from 2001-April

2007 predicted:

Violence will have a lot of effect on the outcome of the

election. Firstly it is a tool of intimidation. By beating

up people like Tsvangirai they are sending the message

that no one is safe. And when word gets out into the

rural areas that you are not safe, this will have enormous

impact. There is already intimidation in past elections by

local tribal leaders who are loyal to the government—if

you don't vote for the government party you won't get

food aid. The president of the Chief's council Senator

Charumbira went even a step further and said traditional

elders should evict those who vote for the opposition.

So if you go into a situation next year, where you are

already expecting drought, in a hotly contested election,

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 9

The Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights

condemns the denial of access to medical treatment of

detained opposition and civic leaders that are in need

of urgent medical attention. ZADHR has been denied

access to those concerned since their arrest on the

morning of Sunday 11 March 2007. Denial of access to

treatment continues to violate the rights of those detained

and threatens their lives.

Notwithstanding a High Court order granted at 8:1_pm

on Monday 12 March 2007 compelling the police to

grant legal and medical access to those detained, the

Zimbabwe Republic Police has denied access to the

injured activities in defiance of the court order. Medical

practitioners that attempted to access those in need of

medical treatment on the night of Monday 12 March

following the granting of the court order were denied

access.

ZADHR remains concerned that the condition of those

who sustained injuries as a result of torture and assault

may be worsened by delayed access to medical treatment.

It is crucial that all those in need of medical attention be

transferred to a medical facility that affords them the best

possible medical care immediately.

Medical Organizations in Africa and internationally

have spoken out against human rights abuses in

Zimbabwe in recent months as well as delays in access

to medical care for victims of political violence and

harassment of Zimbabwean doctors assisting these

victims.

In April 2007, the South African Medical Association

issued the following statement:

Recent events of violence and human rights abuse in

Zimbabwe have grabbed the attention of the world press.

As the South African Medical Association (SAMA), we

condemn any form of human rights abuse and cannot

remain silent on such issues," said SAMA Chairperson,

Dr Kgosi Letlape, in response to international headlines

on the Zimbabwe situation.

SAMA has always advocated for the protection and

promotion of human rights, irrespective of individuals'

political affiliations. "The allegations relating to denial of

access to health care are serious since this is a fundamental

html/archive/hr/070313zadhr.asp?orgcode=zim065&year=0

&range_start=1

human right and entitlement of every person," Letlape said.

The Medical Association is aware of the plight of the

people of Zimbabwe not only through media headlines,

but also through the Zimbabwe Association of Doctors

for Human Rights (ZADHR). ZADHR has highlighted

events where doctors in Zimbabwe are being victimised

and prevented from treating political victims of human

rights abuses.

Doctors' autonomy and independence is a firm principle

which is entrenched in national and international

policies, such as the World Medical Association Code

of Medical Ethics and Declaration on Professional

Autonomy and Self Regulation. "The Hippocratic Oath

will not allow us to compromise these principles," Letlape

continued, "and doctors in all countries must be allowed

to treat patients in need of medical attention, and to

practise medicine without the fear of violence."

SAMA, like other National Medical Associations, have

an essential role to play in calling attention to any

human rights violations. Letlape urged, "The United

Nations' Charter and the Universal Declaration on

Human Rights, of which Zimbabwe is a signatory

country, must be upheld."1_

In October 2007, the World Medical Association

(WMA) adopted a resolution on health and human

rights abuses in Zimbabwe which included calling on

its affiliated national medical associations to publicly

denounce all human rights abuses and violations of

the right to health in Zimbabwe, and actively protect

physicians who are threatened or intimidated for

actions which are part of their ethical and professional

obligations. The WMA resolution also encouraged the

Zimbabwean Medical Association (ZiMA) to commit

to eradicating torture and inhumane, degrading

treatment of citizens in Zimbabwe and reaffirm their

support for the clinical independence of physicians.16

Zimbabwean President Mugabe's response to the

torture and political violence following March 11 has

been to attempt to justify it. "If they (protest) again,

we will bash them again," he declared in a speech in

response to the March 11th violence, "We hope they

have learned a lesson. If they have not, they will get

15. South African Medical Association. Press Release: SAMA

speaks out against human rights abuses. April 5 2007

16. World Medical Association. Resolution on Health and

Human Rights Abuses in Zimbabwe. Adopted by the WMA

General Assembly, Copenhagen, Denmark, October 2007.

Available at: http://www.wma.net/e/policy/a29.htm.

10 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

similar treatment," he said later. Regarding the beating

of MDC President Tsvangirai he said: "Yes, I told the

African heads of state he was beaten, but he asked for

it. I told the police, beat him a lot. He and his MDC

must stop their terrorist activities."17

Medical documentation provides corroborating

evidence of torture and abuse.18 A number of

Zimbabwean health professionals have developed

extensive expertise and are internationally recognized

for their work in documenting and caring for victims

of torture and political violence. In mid-April,

ZADHR19 reported that following March 11, 2007, at

least 49 individuals required hospitalization as a result

of injuries from torture and political violence and

an additional 175 individuals had been treated and

discharged. Injuries included soft tissue injuries, head

injuries, fractures and gun shot wounds.20 International

medical organizations, including the International

Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT)21 and

Physicians for Human Rights, Denmark22 have also

documented several cases of torture in Zimbabwe in

the past.

Ours is the first investigation of political violence

conducted by international health experts since the

March 11, 2007 prayer meeting. Our findings support

17. Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum. Their Words Condemn

them: The language of Violence, Intolerance and Despotism

in South Zimbabwe. May 2007. Available at: http://www.

hrforumzim.com/frames/inside_frame_special.htm.

18. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner

for Human Rights. The Istanbul Protocol. Available at:

http://www.ohchr.org/english/about/publications/

docs/8rev1.pdf; Iacopino V, Allden K, Keller A. Examining

Asylum Seekers. A Health Professional's Guide to Medical and

Psychological Evaluations of Torture. Boston: Physicians for

Human Rights; 2001.

19. For a complete list of publications/documents prepared

by ZADHR see http://www.kubatana.net/html/sectors/

zim065.asp?like=Z&details=Tel&orgcode=zim065

20. Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights.

Update on Assaults, Torture and Health Rights Violations Since

March 11 2007. April 15 2007. Available at: http://www.

kubatana.net/html/archive/hr/070415zadhr.asp?orgcode=z

im065&year=0&range_start=1.

21. IRCT. Organised Violence in Zimbabwe. June 2000. Available

at: http://www.hrforumzim.com/members_reports/

irct000606/irct000606e8.htm.

22. Physicians for Human Rights, Denmark. The Presidential

Election: 44 days to go. January 2002. Available at: http://

www.solidaritypeacetrust.org/reports/pres_election.pdf.

the assertions of other organizations that there has

been an upsurge in state violence since March 2007.

This report contains credible first-hand testimony from

Zimbabweans who have suffered torture and political

violence since March 2007 and provides evidence

that the Zimbabwean government is systematically

deploying torture and violence as a means of deterring

political opposition, with devastating consequences for

health and human rights.

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 11

IV. TRAUMA EXPERIENCED

BY INVESTIGATION

PARTICIPANTS

Nature of Traumatic Events

Experienced

All 24 of the victims reported a history of torture/

political violence within the past year. Twenty (83%)

had experienced torture/political violence on or

since March 11, 2007 (See Table 2: History of Political

Violence/Torture). More than half (63%) reported

experiencing torture/political violence prior to March

2007 as well. All reported a substantial fear of further

violence in the period after March 11, 2007.

Individuals interviewed reported having been

subjected to a number of different forms of physical

torture/abuse (See Chapter V), most commonly

beatings with fists, kicking with boots, or beatings

with objects (shambocks, whips, gun butts). One

particularly common form of torture was falanga--

beatings on the soles of the feet.

Other physical forms of torture/abuse reported

included being shot; stabbed with knives or other

sharp objects; having food, water and basic medical

care withheld; being forced into contact with urine,

feces, and sewage; and being subjected to electrical

shocks.

Individuals also reported a variety of psychological

abuses including verbal abuse, threats to themselves

and their loved ones, and humiliations such as being

forced to undress or drink urine.

Commonly reported perpetrators of torture/political

violence included the police, members of the Central

Intelligence Organization (CIO), "War Veterans," and

ZANU-PF Youth. More than half of the individuals

interviewed (63%) reported having been jailed because

of their political activities. Another 21% reported

a history of being abducted by groups, such as the

Central Intelligence Organization, ZANU-PF Youth,

and War Veterans (see Table 3: Trauma History,

and Chapter V). All of the individuals who were

imprisoned or abducted reported a history of torture.

Health Consequences of Torture/

Political Violence Experienced

All 24 of the individuals examined had clear,

corroborating physical evidence of their torture/abuse.

All continued to suffer from significant physical and

psychological symptoms as a result of their torture/

abuse (See Table 3 and Chapter VI).

In addition to clinical interviews, profound

psychological distress was confirmed by standardized

psychological measures (the Harvard Trauma

Questionnaire for posttraumatic stress disorder

–PTSD- and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25

for depression and anxiety). These measures were

completed by 18 of the 24 individuals evaluated.

Eighty nine percent reported substantial symptoms

of anxiety, 83% reported substantial symptoms of

depression and 76% reported substantial symptoms of

PTSD (See Tables 4 and 5 and Chapter VI).

Many injuries led to persistent pain that was

aggravated by delayed or inadequate access to

healthcare (See Chapter VII).

Among the 15 individuals who were jailed, 7 reported

significant delays in receiving needed medical care

while in custody, and 6 reported being denied legal

services while in custody (see Chapter VII).

12 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

V. STATE SPONSORED

TORTURE AND VIOLENCE

AFTER MARCH 11

Since the events of March 11, 2007, the Zimbabwean

government has brutally and systematically sought

to suppress political opposition with state sponsored

torture and political violence. This was confirmed

in detailed medical/forensic evaluations of 24

Zimbabwean victims of torture and political violence

as well as in interviews with non governmental

organizations, human rights advocates and health

professionals. The violence is targeted not only at

prominent leaders of the political opposition but at

ordinary citizens as well.

Under Zimbabwe's own constitution torture is

illegal.1 Article 15 of the Zimbabwean Constitution

states: "No person shall be subjected to torture or

to inhuman or degrading punishment or other such

treatment." Additionally, Zimbabwe is a signatory

to a number of international treaties, including the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

and the African Charter on Human and People's

Rights that forbid torture and other cruel inhuman or

degrading treatment or punishment.2

Political Violence and the Events of

March 11

On March 11, 2007, the MDC held a prayer meeting in

Highfield, just outside Harare. The following accounts

relate to the subsequent torture and political violence

perpetrated against individuals who attended the

prayer meeting.

1. Constitution of Zimbabwe, Articles 15. Available at:

http://www.kubatana.net/docs/legisl/constitution_zim_

070201.doc

2. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. res. 2200A (XX1), 21 U.N.

GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A.6316 (1966), 999

U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, acceded to

by Zimbabwe, May 13, 1991, Article 7; African Charter on

Human and People's Rights, adopted June 27, 1981, OAU doc.

CAB/LEG/67/3rev.5.21.l.LM.58 (1982), entered into force

October 21, 1986, ratified by Zimbabwe in 1986, Article 5.

The case of KF

KF, an MDC leader and organizer of the March 11 rally

described the scene as follows:

Unfortunately before the prayer meeting could start,

we saw police details all over the place. They ordered

us to disperse, claiming we are not coming for a prayer

meeting but a political meeting. As we resisted, they

started beating us. They indiscriminately started beating

people with clubs, using tear gas. Then there were some

water cannons. So there was confusion all over the place.

KF described subsequent indiscriminate shooting

by police, including witnessing MDC member, Gift

Tandare, shot and killed:

They started firing live ammunition into the crowd.

Eventually, they shot Gift Tandare in front of me. I tried

to help him but it was too late. From then, I could see that

he was dead. I called his name, but he could not respond.

I told my other colleagues that our friend has died.

When KF learned that MDC president Morgan

Tsvangirai had been arrested and beaten, he went to

the police station where Mr. Tsvangirai was being held:

When I asked why the president was being beaten, I

was also beaten severely [by police] with sticks, the

butt of the gun, and kicked with boots. As they beat

me they said 'We are beating you for trying to unseat

the government.' We were detained there overnight,

myself and the others. Then the following day we were

transferred to the Harare Central Police Station. Then

we were again tortured, this time by members of CIO

(Central Intelligence Organization). They were in plain

clothes. We were in their office at the time. This time,

they beat me in my genitals, with a small rubber stick.

I was ordered to remove all of my clothes. They beat me

and wanted me to testify on other plans that the MDC

was engaging in.

While he was in custody, KF was blindfold and

forced to drink a liquid that he thinks was urine.

Subsequently, KF was released without any charge.

KF also described three previous severe beatings

related to his political activities. Following his most

recent beating, KF continued to suffer from frequent

headaches. He also noted decreased hearing in one of

his ears, having injured his ear when he was thrown

against a wall. Physical examination revealed multiple

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 13

scars consistent with the events he described. This

included several well-healed thin linear scars from

the stab wounds, as well as multiple scars on his back

and a smooth indented scar on his left anterior lower

leg, consistent with an injury from being kicked. A

perforation in his left tympanic membrane (ear drum)

was noted and hearing in his left ear is decreased

compared to the right.

Fearing for his safety, KF remained in hiding following

his most recent abuse. Government authorities

continued to come to his house looking for him:

They threatened my family, almost on a daily basis. They

came to investigate trying to find out my whereabouts.

They said to my wife if she was not going to reveal my

whereabouts, they would arrest her, until I surrendered

myself to the police.

KF suffered from a number of psychological

symptoms of depression and post traumatic stress

disorder (PTSD) including feelings of sadness,

difficulty sleeping and frequent nightmares. He is

intensely worried about his family:

The trouble that my family is facing is very upsetting

to me. I am the provider for the family. In nightmares,

I imagine being beaten again in the police cells. I think

about it a lot when I am awake too.

The case of RP

RP is another victim of the political violence on March

ll. RP is a 35 year old male who works for the MDC

and who described being with Morgan Tsvangirai

when he went to a police station to visit other MDC

supporters who had been arrested:

When we had arrived, we were outside the police

station and we were mobbed by police officers, who

were shouting vulgar words at the MDC president.

Because they were advancing toward us we ran into the

police station.... we saw all the other MDC supporters

and civic organizers. They were all lying down and

being beaten, including Sekai Holland, Grace Kwinje,

Tendai Biti (the Secretary General), Nelson Chamisa

the Information and Publicity officer for the MDC,

and Lovemore Maduku the Chairman of the National

Constitutional Assembly. They were all lying down face

down being beaten by many police officers. I saw this

with my own eyes. They were using all sorts of weapons

like shambocks (whips), sticks and some metal iron bars.

When we arrived there, Mr. Tsvangirai was told to lie

down. He was forced to lie down. And immediately before

he lied down, a female police officer started to beat him,

and the rest joined in. They said 'You are the leader of

these people and we want you to tell Blair and George

Bush to remove the sanctions and to tell them they must

leave Zimbabwe alone.'

Subsequently RP was beaten himself:

They started beating me all over my body. They beat

me on the head, on the ribs on the shoulder-everywhere

all over the body, with the sticks iron bars, some were

jumping on my ribs to the extent that I passed out 3

times. Then they told me, 'You must go and tell the

MDC supporters that the only president is Mugabe.

Tsvangirai is not the president.'

Violence Against MDC Members and Local

Organizers: The Cases of CJ and SP

Violence on March 11 was directed at local MDC

organizers and ordinary citizens in addition to

prominent MDC leaders. For example, CJ, a thirty

year old woman and an MDC member who holds no

position with the MDC, was with a group of people

planning to attend the public prayer service when she

was arrested.

We were taken by the police to the Highfield police

station. They were accusing us of being Tony Blair's

people and they wanted the money given by Tony Blair.

I was hit all over the body. I was lying down on the

ground. They would beat you harder if you cried out. I

was beaten with iron bars, batons and open hands. After

one hour we were taken to Central police station. I was

already in great pain. We spent all day at Central police

station. I was not beaten there.

Subsequently, CJ was taken to another police station

where she was held for 3 days.

Then they were shouting at us there 'What do you get

from Morgan Tsvangirai?' We were not given water or

food for 3 days... We were in separate cells. I asked for

food, and they said 'No you are not given food.' There

was no bed, I slept on the floor. I was in great pain. I had

pain all over my body. There were no blankets. I wished I

would just die because I was in such pain.

In addition to suffering pain, CJ also described having

blisters on her legs and bruises on her back from the

beatings. At the time of evaluation, CJ continued to

14 / Torture and Political Violence in Zimbabwe

suffer from pain in her legs and difficulty walking.

She had lost 10kg. She described feelings of

fearfulness, difficulty sleeping and concentrating

and frightening memories of her abuse. She

appeared numb and demoralized with slow, weak

speech and gestures, avoidant eye contact and

slouched posture. She provided limited details or

spontaneous expression during the interview and

presented as profoundly depressed:

I still have the memories of what happened, especially

when I see police. I am afraid. I have nightmares

nearly every night about what happened in the police

station. I am crying. Whenever I hear footsteps

outside, I feel scared, and I jump. When I was in the

cells, I felt the death spirit. That thought still comes

back to me.

Physical examination confirmed the beatings she

described. Multiple linear hyperpigmented (i.e.

darker than the surrounding skin) scars were

present on her back. She had multiple nodular scars

on her legs and a prominent scar on her left leg at

the site of her skin graft. Her gait was somewhat

unsteady, and she had difficulty bearing weight on

her left leg.

Another MDC member, SP, who is a local MDC

organizer, was also arrested on March 11. Prior

to March 2007, SP had been arrested and tortured

approximately 10 times. On March 11, 2007, SP was

arrested near Highfield along with several other

MDC members:

We were taken to Harare Central Police Station. Then

they started questioning us. They took me to a back

room and they came with the electric cords, and put

the cord on my penis and shocked me for a second. I

never received such a pain especially on my penis. It

was terrible. They were saying 'Why were you going

to the rally? Who authorized you to do?' They shocked

me two times. They didn't beat me so much, but the

electricity was very painful.

SP remained in jail for 3 days. Before being released,

SP was ordered to pay a fine for inciting people to

attend the rally, which SP noted had been allowed

by the Zimbabwean High Court. Subsequently,

SP reported he had learned that the CIO had been

looking for him and other local leaders on suspicion

of being involved in petrol bombings of police

stations, which he denied:

They arrested more than 12 activists and they are still in

prison. After they put them in prison, they tortured those

guys. We saw pictures of them in the court and we saw

the pictures they had blood and swollen heads...They are

torturing and making sure you won't do anything. In the

past- in 2000- I was forced to sign an affidavit, putting

allegations on myself-like beating police officers. They

were not truthful.

Fearing for his safety SP fled to South Africa:

If I go back they will definitely arrest and torture me. If

they arrest me, they will definitely torture me until I say

what they want me to say-that we were doing all of those

activities-I wasn't doing any of that.

SP described experiencing chronic pain in his right leg

and hand since they were broken by police in incidents

when he was arrested prior to 2007. He also frequently

experienced headaches. He was haunted by memories

of his trauma:

I have bad dreams especially these days. It is terrible

I dream about all the people being beaten. I feel very

nervous. I am afraid even of my shadow walking in the

street.

I'm very worried for my family. They can do anything.

Last time they beat my wife, she had a miscarriage. I

haven't been able to communicate with my family. What

they are doing is trying to put people who are influential

in prison so they can't do anything and then beat them.

When I was arrested, in March, they said 'We will make

sure that you never lead this country because you never

went to war.'

On physical examination, SP was found to have

a scar on his forehead and a well healed smooth

elliptical hyperpigmented scar on the back of his right

wrist consistent with the history of the beatings he

described.

Violence by Perpetrators Other Than the

Police: The Case of YD

Police were by no means the only ones perpetrating

violence on March 11. YD, a 29 year old male who

worked in the national MDC office was stopped by

police at a road block en route to the prayer rally at

Highfield. He was subsequently turned over by the

police to members of the Youth militia:

A Crisis in Democracy, Health and Human Rights / 15

When we got there the roads were sealed and the police

were beating people with baton sticks and the butt of

the guns. I saw this. We were stopped by police officers

and then taken by guys in civilian clothes. One of them

showed us an official card of the youth militia and asked

if I had one (he did not). I was handcuffed by the police

with my hands behind my back the moment I was taken

from the roadblock. The police put the handcuffs on and

turned me over to the youth group.

Subsequently, YD was taken by the 6 men in civilian

clothes to the Southerton police station:

They had guns. Then they made us stay outside the police

station, and waiting for a vehicle. Then we were taken in

a vehicle to another place. I was blindfolded. They were

shouting telling me, 'You are going to meet Tsvangirai in

hell. Tsvangirai is also dying. Tsvangirai is being beaten

right now, who are you? We understand Tsvangirai is

causing trouble, we have been given information that you

have been trained to fight the government, and it was

part of the strategy to destabilize the country. Therefore

you are a sellout for Tsvangirai.'

At the second location, YD was placed alone in a room.

He was forced to remove all his clothing except his

underwear. His blindfold was removed, but his hands

were still cuffed behind his back. Then he was beaten:

They hit me with the baton sticks all over my body,

including my shoulders and on the bottom of my feet. I

was very weak. They said, 'This person won't talk, we

must try some other means.' They said, 'Do you know

what is torture?' A woman came into the room. She said

'I am a mother-I can't accept this kind of beating.' They

put my head inside her dress and said 'What do you see?'

I said I can't see anything. They kept saying 'Why are

you saying nothing?' and kept beating me, so I said I can

see red pants. Then the lady hit me very hard across my

face and said 'You are telling people what I am wearing.'

YD was told that his torturers had information about

him and his family, including where his parents lived

and that his sister was a government employee. He

reported that his sister had previously been harassed

at work as a result of his activities. He was told that if

he gave them information about the MDC, he and his

family would not be hurt. Otherwise, they would be

harmed:

They told me the name of my father, my mother, and

where my sister worked. They said we know everything

about your family. So you must know your life is really

shit, either for you or your family. If you don't tell us

what we want to know –they wanted to know about the

MDC and what it was planning.

Subsequently YD was hit on the head and lost

consciousness:

The next thing that I remember, I woke up. I was lying

along the road outside of Harare. I was now wearing

my clothes. I was soaked with blood. I suspect that they

thought I was dead. Somebody who was driving along the

road shook me and I woke up. They told me I am badly

injured. I looked at my clothes. I could feel too much pain

from my head and I had a very big wound.

YD described significant difficulty obtaining medical

care for his head wound. (See Chapter VII)

Subsequently, he learned that authorities were looking

for him:

My [relative] got a message that there were some people

at my place looking for me and wanting to arrest me

saying I was involved in the violence and part of the

people who had dropped petrol bombs [on police stations].

But I was being beaten by those people at the time when

the bombing happened.

Fearing for his safety, YD decided to leave for South

Africa. His family was also living in hiding. "I sent

them to the rural area because their life was in danger.

We couldn't stay together."

After his beatings, YD continued to suffer from